Over the last thirty years or so, the analytic potential of computers has been increasingly applied to language, and the language of literature. The field of computational stylistics has flourished across research communities, albeit until recently focussed primarily on English literary texts. The objectives of many scholars working with the quantitative, processing power of computers has been authorship; specifically, to establish the legitimacy of the purported author of a text or texts. The best-known area of (ongoing and often heated) investigation relates to Shakespeare.

However, computational stylistic work isn’t solely about authorship attribution. As just one example, Craig and Hirsch’s recent (2017) publication testifies to the potential directions and avenues of quantitative approaches to early modern literature. And, despite the remit of the attribution team on the Aphra Behn project being precisely that (i.e. evaluating the traditional attributions of texts to Behn, however shakey and speculative), our initial work on Behn’s language has not considered authorship attribution at all. Instead, we have focussed on establishing the stylistic markers of her writing, specifically her dramatic writing, and tracing their evolution over the course of Behn’s career and lifetime. Our article ‘Style and Chronology: a stylochronometric investigation of Aphra Behn’s dramatic style and the dating of the Young King’, which appears in the most recent issue of Language and Literature, provides the first published report on the style and attribution analysis undertaken on the Aphra Behn (E-ABIDA) project.

The article documents our preliminary investigative work which seeks to get a handle on Behn’s dramatic style. Her drama is copious, and presents some particularly acute challenges relating to dubiously attributed texts; challenges we will discuss in more detail in a future post. Significantly, from the perspective of computational stylistic methods, Behn’s dramatic works span a 20-year period, and the distribution of genres (tragedy, comedy, tragicomedy) is uneven across this time-frame. Whilst studies suggest that the authorial signal more often than not shines through the other facets of style (like genre and time-period) (Burrows and Craig 2002), the aforementioned properties of Behn’s literary data means that it is desirable to obtain as much information as we can about what typifies Behn’s language in her plays. Our recent investigation considers whether Behn’s work has a chronological “signal”; that is, can the computational analyses differentiate her plays according to the time period in which they were written – the ‘stylochronometric’ part of the study. In this blog post, I discuss the main reasons for starting with this chronological focus, and offer some of our initial experiences of negotiating Behn’s language through this quantitative lens.

Theoretical Insights

Scholarship on Shakespeare and other writers has observed, explored and debated the chronological developments across literary careers (and Behn is no exception: the fast-changing political and economic context of Restoration theatre entailed that Behn had to be reactive (or anticipative) to sustain her career as a playwright). What is interesting, from a linguistic and cultural perspective, is the direction of chronological developments, be they early modern or from other literary periods in history, identified in individual authorial practices, on the one hand, and their intersection with cultural trends, on the other. Rybicki (2015) makes an important point when he observes how these two levels (micro- and macro-) overlap, with lifespan changes woven through cross-generational trajectories of change. We might consider this process analogous with a flock of birds; no one bird controls the whole flock, but instead each makes minute adjustments (anticipative and reactive) to ensure the continuation of their flight. The relationship between individual and social process in language change (literary and otherwise) is one that fascinates me, and this is an area to which I believe computational stylistics can really contribute.

In our analysis of Behn, we focus on Behn’s changing style within the framework of her lifespan – looking at what develops and how. Since this was an early study, we were not in a position to consider the relationship between Behn and her Restoration colleagues. However, we have since prepared extensive comparative corpora and hopefully we will be able to contextualise the changing stylistic preferences of one writer with those of many others. The ongoing project, Mind-Bending Grammars at the University of Antwerp provides a valuable resource with similar objectives, albeit focussing on changes to morphosyntactic (grammatical) features. Excitingly, their investigation – which uses EEBO-TCP as its corpus – includes the grammar of Aphra Behn. Some of their early findings suggest she was among the more progressive individuals in the acquisition of innovative grammatical structures. These developments of quantitative methods and techniques, which can pull together and scrutinise the intersection of literary, linguistic and cultural change, presents valuable opportunities for how we theorise and understanding temporal developments in language and style.

Practical Applications

Identifying the chronological style of Behn also has more practical applications. By identifying key markers of Behn’s style that can be associated with different temporal periods, we are in a better position to judge the linguistic results produced for the works of questionable origin. Within the drama corpus, the majority of the dubia is dated to the late 1670s, placing it – we know now – at an apparent transitional period between Behn’s early (e.g. Forc’d Marriage, Dutch Lover) and mid-period (e.g. The Rover) plays. It will be interesting to establish the extent to which the developments identified in her dramatic works are apparent in her other writing such as her poetry and her fictional prose. Studies (e.g. van Hulle and Kestemont 2016) have shown that writers working in multiple languages do not necessarily show synchronous change. How this relates to writers, like Behn, working in different genres remains to be seen.

Reading the Numbers

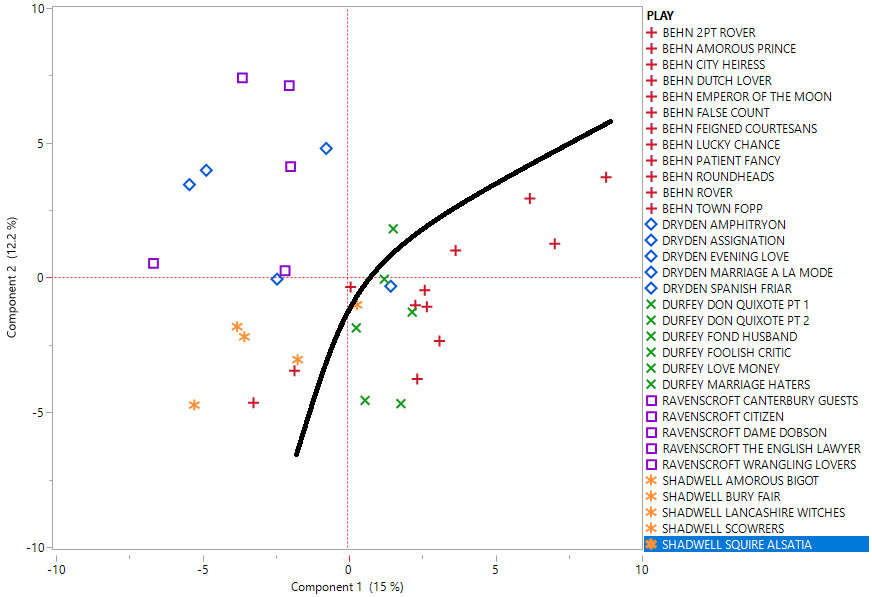

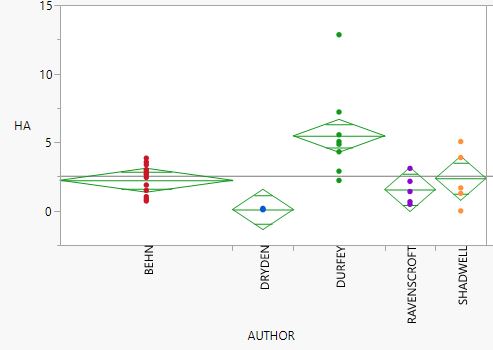

The investigation of Behn’s chronological style has also taught us a valuable lesson in what computational stylistics can, and cannot, provide by way of answers. Whilst the statistical findings are empirically robust, the results of exploratory tests such as Principal Components Analysis require careful interpretation by a human eye (for a gentle introduction, see this ‘PCA 4 dummies’ guide). The stylochronometric investigation sought to test the veracity of Behn’s claim in the dedicatory epistle, published with the play in 1682, that The Young King was in fact the earliest of her dramatic works. The computational analyses therefore had two objectives: firstly, did Behn’s dramatic works convey a sufficiently clear temporal signal in terms of their stylistic properties and secondly, where did The Young King position itself when analysed using the temporal signal criteria.

Using exploratory statistical methods, such as PCA and cluster analysis, Behn’s dramatic works were found to have a chronological signal – on the basis that the works organised themselves into near-perfect date order using the linguistic criteria (e.g. most frequent words). This meant that the computational stylistic investigations had the potential to shed new light on Behn’s statement concerning the dating of The Young King. In an ideal world – the stylistic equivalent of a laboratory experiment, with clean surfaces and no confounding factors – the results would have provided a clear-cut indicator of the temporal markers of The Young King and its chronological position in Behn’s dramatic outputs. However, any study working with historical data has to confront the less-than-desirable make-up of the extant evidence; an example, perhaps, of what Labov (1994: 11) famously called the ‘bad data’ problem in the field of historical sociolinguistics. In our case, Behn’s dramatic output disproportionately favours comedies (12 firmly attributed). Tragedies (1) and tragi-comedies (3) are far less frequent. This is not an issue in itself, necessarily, until you wish to compare texts representing different chronological sub-periods and the genre signal starts to interfere with the temporal and authorial elements of the results.

Making sense of the results for The Young King analysis was therefore challenging. The extensive combination of tests – PCA, cluster analysis, Zeta – provided rich and overlapping results for the stylistic similarities between Behn’s plays, but it was difficult to assess the cause of those similarities. For example, the cluster analysis based on 300 most frequent words in Behn’s drama (reproduced from Evans 2018) shows how The Young King clusters most closely with Abdelazar – Behn’s only tragedy.

Cluster Analysis of Behn’s plays and The Young King (300 Most Frequent Words)

The other clusters on the graph show how Behn’s drama group into temporal periods: early (up to 1673), middle (1677-1682) and late (1682-1690). Is this grouping because Behn was stretching the truth regarding the early dating of The Young King? Abdelazar was first performed in 1676-7. Or is it becaue of genre similarities? PCA analyses, such as the one shown here, offer a similarly complex picture: The Young King and Abdelazar again group together, but whether this is because of chronology and/or genre is not clear.

PCA of Behn’s plays and The Young King; 300 most frequent words.

Our current thinking is that, if the similarity between The Young King and Abdelazar is wholly attributable to genre, then we would expect to find a equivalent proximity between The Young King and Forc’d Marriage – which is not only a tragicomedy but also one of Behn’s earliest plays, thus carrying a double-whammy of stylistic signals (genre, time-period) if Behn’s dating claim for The Young King is accurate. This association does not emerge in any of the tests we conducted. On this basis, it seems more likely that the version of The Young King we have today (published in 1682) was at least heavily revised by Behn later in her career, leaving stylistic traces more typical of her mid-career writings. If our interpretation is accurate, then this provides a new perspective on Behn’s understanding of the likely reception of her work by Restoration audiences, and some of the strategies required to maintain a successful literary career.

Next Steps

One of the most important lessons of our early investigations into Behn’s style is that, for the most part, the results of computational stylistics are indicators, not pronouncements. There is an art, a humanity, to the reading and understanding of quantitative statistical trends – to recognising and appreciating the nuances in why Behn’s language use looks as it does, whether that’s pronouns, verb choices, or sequences of letter-forms or words.

As we go forward with the attribution analysis proper, our investigations will strive to take these early findings on board, and incorporate them into our methodological decisions (i.e. what texts to compare/contrast; how to organise different texts as “representatives” of a particular time-period or genre), our theoretical perspectives (lifespan literary change is a complex but definite and quantitatively chartable phenomenon) and our understanding of an author’s position within wider changes within the linguistic and cultural systems.

Watch this space for more reports on the attribution analyses.

Links:

Mind-Bending Grammars Project; led by Peter Petre, University of Antwerp

https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/projects/mind-bending-grammars/

PCA 4 Dummies

https://georgemdallas.wordpress.com/2013/10/30/principal-component-analysis-4-dummies-eigenvectors-eigenvalues-and-dimension-reduction/

References:

Burrows, John, and Hugh Craig. 2012. ‘Authors and Characters’. English Studies 93 (3): 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2012.668786.

Craig, D. H., and Brett Greatley-Hirsch. 2017. Style, Computers, and Early Modern Drama: Beyond Authorship. Cambridge ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, Mel. 2018. ‘Style and Chronology: A Stylometric Investigation of Aphra Behn’s Dramatic Style and the Dating of The Young King’. Language and Literature, May. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947018772505.

Labov, William. 1992. Principles of Linguistic Change. Vol. 1: Internal Factors. Language in Society 20. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rybicki, Jan. 2016. ‘Vive La Différence : Tracing the (Authorial) Gender Signal by Multivariate Analysis of Word Frequencies’. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31 (4): 746–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqv023.

Recent Comments