The new Cambridge Edition of the Works of Aphra Behn (forthcoming) is informed by computational stylistic approaches to Behn’s style and authorship, combined with traditional literary approaches to attribution.

A key requirement for computational stylistic investigation is the corpus of texts for analysis: works by Behn, the dubia, and writings by her contemporaries for comparative analysis. Decisions made in the compilation and preparation of those texts affect the linguistic material that is available for computational analysis, the kinds of results that are obtained, and thus the ways in which the findings can be compared with, and interpreted against, other scholarship (whether more traditional literary analysis or other computational work). Due to the importance of transparency and replicability, the following discussion provides a brief outline of the development of these corpora, the challenges and rationale underlying our decisions, and our future intentions for the further development and distribution of the texts. The focus is on the treatment of the texts, rather than the selection of their contents (watch out for a future update on the latter!).

Behn’s drama corpus (created in 2016):

Behn’s dramatic works are relatively plentiful: sixteen plays with secure attribution (dating from 1670-1690), alongside the plays of dubious attribution. There are no manuscript originals and – in most cases – only one lifetime edition of the printed text. The original corpus of Behn’s drama was created in 2016. The raw texts were mainly sourced from EEBO-TCP. Where the digital texts were not available, they were manually keyed by the General Editors.

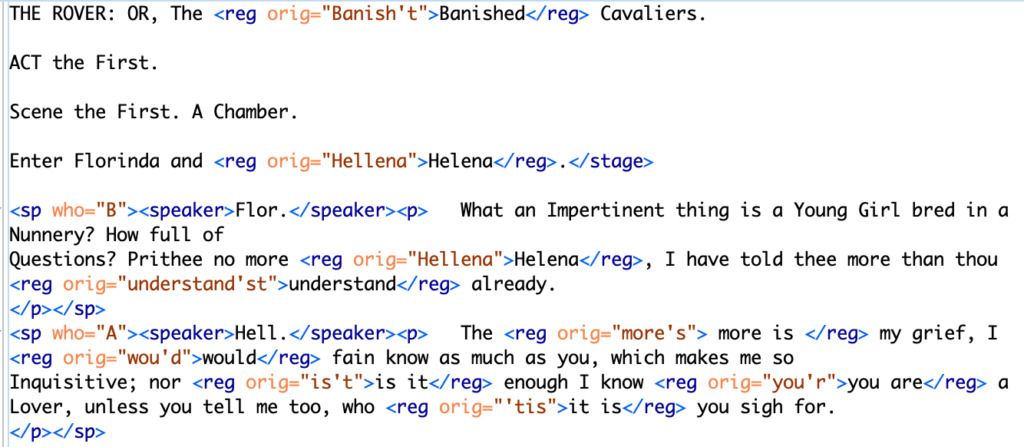

The computational approach to style and authorship separates the full texts into their constituent linguistic parts – typically individual words, but this can also be word sequences (n-grams) or character sequences – for quantitative analysis. In our investigation of Behn’s works, we use the software package Intelligent Archive, which relies on XML tags to identify the parts of a text to include in analysis (see screenshot, below). This entails that features such as stage directions and speaker tags can be automatically excluded from the word counts for the dramatic texts. The unwanted paratextual material, including prologues, epilogues and songs, is placed in the TEI header, as IA does not include header information when extracting the lexical data. All of the dramatic texts are encoded using TEI Lite protocols, prepared using Oxygen XML Editor. The XML mark-up is therefore not as extensive and detailed as that used in, say, a digital edition, but it is sufficient for the requirements of the computational tests.

Because the computational stylistic approaches used in our investigations are word-based, it is necessary to regularise the spelling of texts first printed in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Behn’s drama was regularised using VARD (a program developed by Alistair Baron) by Mel Evans and an RA, Georgia Priestley. In the first pass through Behn’s drama, back in 2015-16, this was done before the XML mark-up of the rest of the text. Unfortunately, this order of preparation makes recovering the original spelling of the text (after mark-up) somewhat convoluted; the process has been changed for subsequent texts and a future iteration of the Behn corpus will address this issue prior to their public release (see below).

Our regularisation choices reflect practices employed in previous studies of style and authorship, particularly in relation to early modern plays, as well as taking into account the particularities of the printed texts themselves. In brief, the regularised Behn drama corpus expands contractions (e.g. don’t to do not) on the basis that these may be the decision of the compositor, rather than Behn herself; unfortunately, there are no manuscripts available to check her preferences in a dramatic context. Other principles include regularising second-person verb endings (e.g. knowst to know), but preserving pronouns (you, thou); this decision reflects the potential skewing effect of pronouns in authorship analysis. Whilst pronouns can be treated as stopwords and ignored in the tests, the morphemic differentiation in verb-endings is more difficult to exclude comprehensively in this way, hence their regularisation at the text preparation stage.

Spelling regularisation is not a neutral process, as it necessitates judgements about how orthography and the lexical unit (a word) is conceived. There is no standard way of regularising early modern spelling – in part because it is so variable across time, genre and medium (i.e. print and manuscript) – which entails that comparisons between corpora are inevitably affected by different regularisation principles. The purpose of the regularised text (e.g. for undergraduate study vs. computational analysis) also shapes the decisions made. Thus, the potential significance of variation of regularisation is something we are addressing in subsequent iterations of the corpora and associated analyses.

Behn’s Drama Corpus (2018) and the contemporary Restoration drama corpus (2017-8):

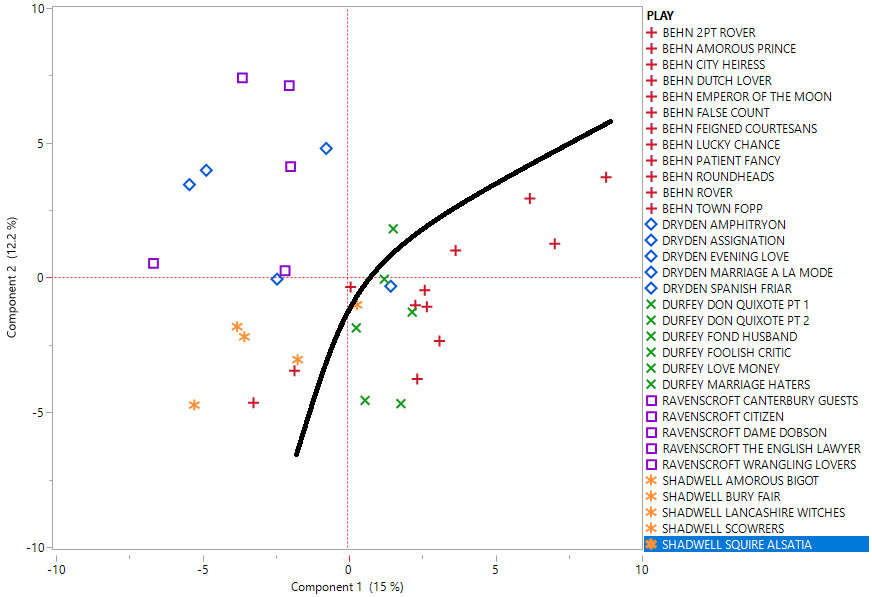

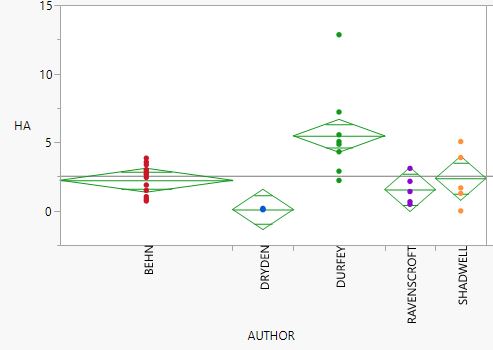

In our current text preparation process (from 2017 onwards) the XML is done first, and the VARDing (spelling regularisation) is done second. This means that we have an original-spelling text to work from, with full mark-up, as well as versions with regularised spelling (with and without regularisation tags). This work continues to be undertaken by Mel Evans and postdoctoral research associate Alan Hogarth. At the time of writing there are 80 plays in the comparison corpus. The majority are works by Behn’s contemporaries (e.g. Thomas D’Urfey, John Dryden, Edward Ravenscroft) but it also includes those who preceded her – and provided source materials – such as Thomas Killigrew and Richard Brome, as well as those who succeeded Behn, some of whom were acquainted with her works, including Mary Pix and Charles Gildon. The temporal breadth is important both to identify and account for changes in theatrical fashions and developments in authorial style over time, as they pertain to Behn and works attributed to her.

Many of the seventeenth-century play texts were taken from EEBO-TCP, with the transcriptions checked and edited for accuracy with the base-text. Some were generously shared by the Visualising English Print (VEP) team, which meant that the dramatic texts were already regularised using VARD. The VEP spellings were updated to follow the regularisation system used in the Behn corpus. Other plays for earlier decades have been kindly provided by Hugh Craig; again, some differences in formatting and spelling regularisation meant that further editing was required to provide greater uniformity with the Behn corpus and other texts.

In summer 2018, the Behn corpus and a sub-set of the contemporary drama was updated to produce versions with regularised interjections (a linguistic category incorporating a lexical unit that stands as a discrete discourse unit such as oaths and exclamations); for instance s’wounds and zounds are regularised to zounds. This enables a more robust comparison of this facet of Behn’s language with that of her contemporary dramatists (Evans, under review). These versions of the plays exist alongside the previous iteration.

Other changes have been made to the 2016 corpus of Behn’s drama, reflecting our findings, the developments in analytic approach and the software used. It appears that Stylo for R, for example, reads content in the TEI header (even when ‘xml plays’ is selected), so plain text versions of the drama corpora were made using Xpath to extract only the dialogue for use with this software package.

We appreciate that the formatting and regularisation processes change the complexion of the data, potentially in quite significant ways in terms of the lexical items available for quantitative analysis. For example, don’t and do not in a corpus entail a greater variety of forms than if all texts are regularised to do not; in the latter scenario, the contracted form is removed from the orthographic repertoire, which might boost (artificially, in a sense) the number of not forms in the corpus. It will be interesting to establish the impact the different regularisation decisions have on the computational results, and this is an aspect we are presently investigating.

Workflow (2019):

Our work on the drama corpus is now informing our preparation of other texts for computational analysis. This includes works by Behn, the dubia, and the writings of her contemporaries in the genres of correspondence, prose and poetry. The workflow for the preparation of these text is as follows:

- Source the text in digital format (plain text) e.g. EEBO-TCP or an existing transcription from other reputable sources. When no reliable transcription is available, the text is be manually keyed by the editorial team.

- Add TEI Lite XML tags to the original spelling text

- VARD the marked-up files, including the following principles:

Expand contractions, regularise interjections, regularise second-person verb endings (e.g. knowest > know)

- Use the XML version to create a stripped, plain-text version of the main text.

Iterations are saved at points 2, 3 and 4.

We will provide more information about these new corpora later in 2019.

Future Plans (2020-):

Following the conclusion of the E-ABIDA project, the plain text files for the complete drama corpus (including Behn, contemporary and dubia works) will be made available in both original and regularised spelling via the project website. It is our hope that other researchers will use these resources to enrich the study of Restoration drama and literature.

Recent Comments